Writing about teaching is like dancing about a government shutdown.

Yet I write. And dance.

There is that tired adage of “Those who can’t do, teach,” to which I counter that teaching is the more regenerative “doing” of the two. And to do both at all is worth a lifetime of striving. There are plenty in academia that view teaching as the grind they have to endure in order to have institutional support, steady income and health benefits. The institutional structure of universities is set up to reinforce the idea of an intellectual hierarchy: at an R1 school there is a low teaching expectation vs. a high research (read: publication and/or exhibition) threshold. At a small liberal arts college there would be the reverse: a high expectation of exceptional teaching ability, and less pressure to have cranked out two books by tenure. And then there’s the-everything-in-between institution, which is where I’m at. As one of the majority nontenured faculty my research expectations are nil, but the reality is you can’t be a decent teacher of art without a robust engagement in said arts, so I do both.

Adjacent to that view of teaching as a grind is a commensurate belief that you should always be wishing you were a full-time artist instead, never having to sully the art practice with the necessity of teaching. I don’t understand this at all. The one always informs the other, and the people that know very little about the things that I know exponentially more about end up teaching me continually. And the steady astonishing of myself by them is what keeps me imaginatively fueled. If art is a series of problems to be solved in a myriad of ways, then teaching is the art that never runs out of unique problems to figure a way out of.

Enjoying this post? Consider leaving a comment, hitting the applause button at the end of the post, or better yet, signing up to receive posts emailed to you directly as they are published. It means a lot to know someone is reading, and that what I write resonates with anyone.

I want to share a couple pedagogical things that I practice:

—One that usually works at keeping my enrollment numbers high and gaining some degree of intellectual buy-in from my students starting on the first day of class

—The other that I only employ in my Intro to Photography class but succeeds wildly at creating conditions for empathy and peer bonding, which often holds over into upper level classes that the same crew of students will end up taking with me.

Both were great ideas from other people that I’ve extended upon over the years.

#firstdayfirstimage was an initiative that began in 2017 by a cohort of faculty peers at the University of South Florida, various institutions in Chicago as well as a smattering of other places. The idea was to engage in a soft re-writing of "the canon" in a more meaningful way than making having a day of class dedicated to women, minorities or non CIS-binary identifying folks. The hashtag was begun as a way for art educators to cross-reference what other peer faculty were showing; to create a database of things to consult to keep the momentum of the project going.

The gist of it is this: the first thing you do on the very first day of class is not hand out the syllabi, take attendance or attempt a dreaded ice-breaker. The first thing you do as a teacher of art on the first day of class is give them something to look at, without context (at first) and then engage in a conversation about what it is they see.

The undermining of institutional power structures comes in the form of the students not knowing that what you are showing is an artist not from the chosen caste/class: ideally the artist being shown would be someone that existed in one or more margins of dominant White and Western culture. I have modified that in my classes to being a living artist working with issues representing the times in which we live. I don't make a point of virtue-signaling that it's a Black/Queer/Arabic/Anything artist. I just find a high-res version of a single work and project it on the screen in a darkened room of 16 people who are all strangers to one another. And then I continue to work similar subsets of artists into presentations and histories of art the rest of the semester.

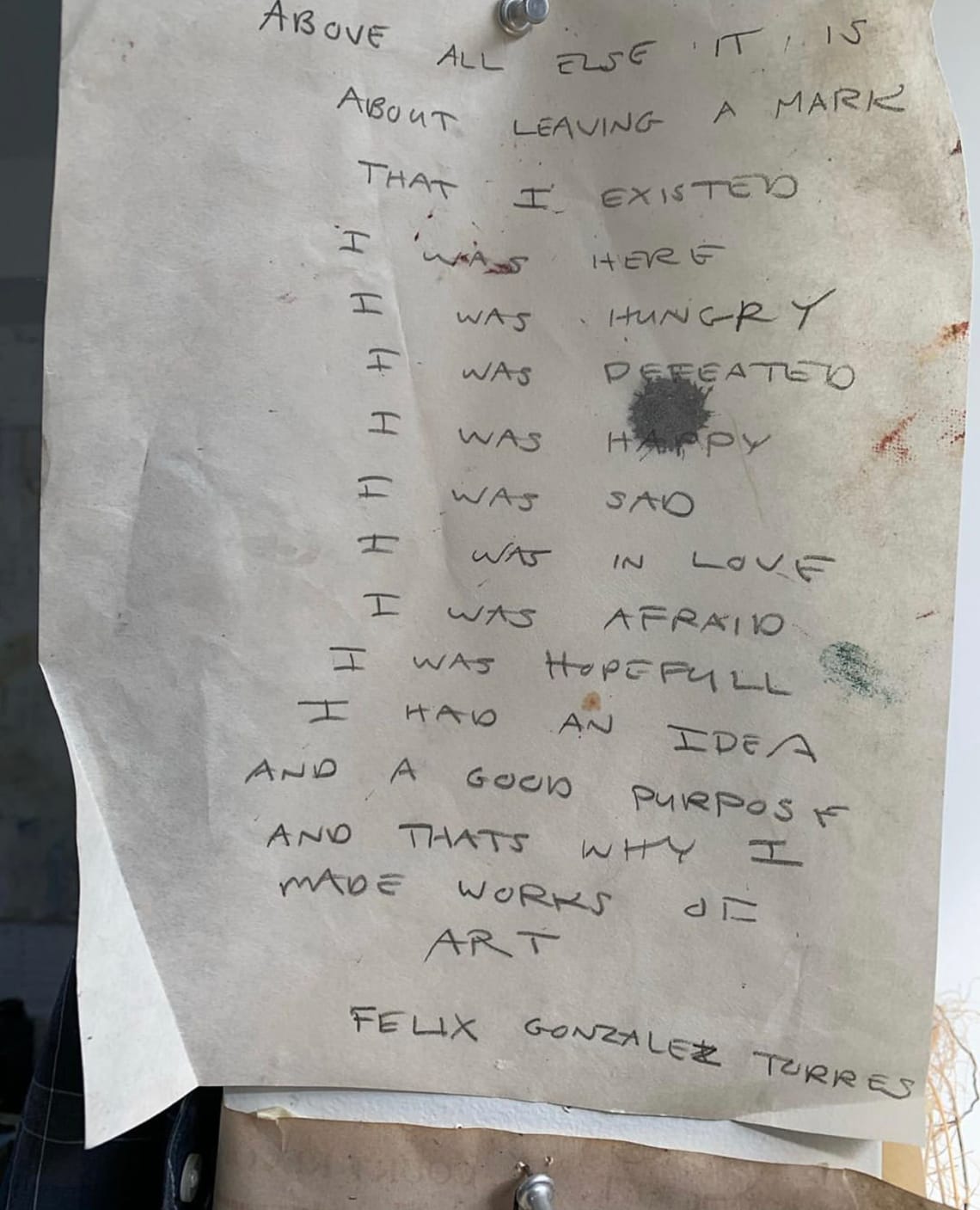

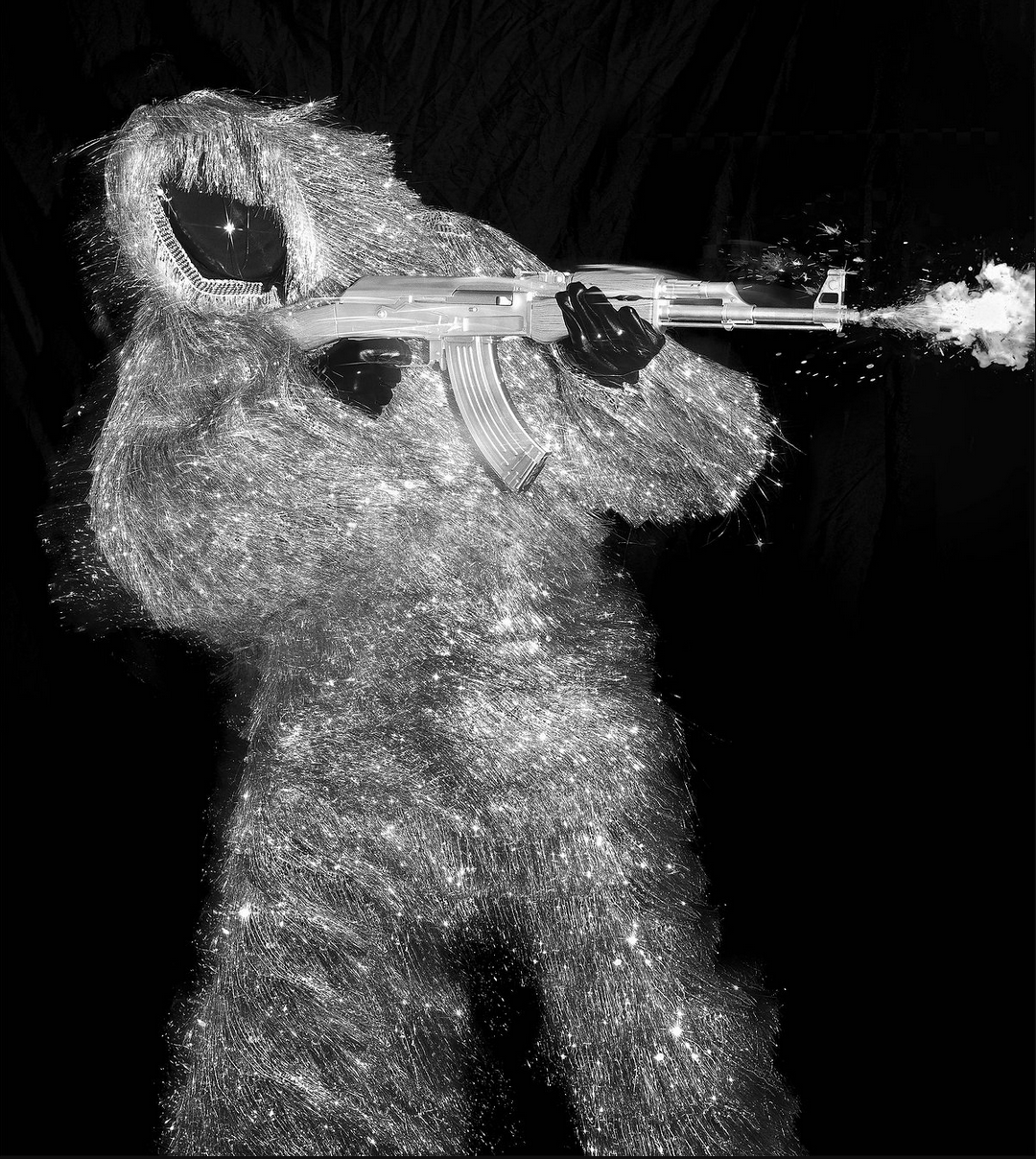

Here's an example:

It's an arresting image, right?

I projected this work on the first day of my Intro to Photography class this fall. I engage in what's termed "Visual Thinking Strategies" where I tell them that I want them to describe what it is they see to me—not what they think, feel or interpret it to mean. Not yet, anyway. I say that I might probe their observation with a follow-up question: what in the image makes them say that? We will talk for some minutes, looking closely and looking again with each voiced noticing.

"The figure is firing a gun."

"The gun looks like it's been spray-painted white or metallic."

"The figure does not read as male or female."

"The figure reads to me as more female than male."

Me: "What makes you say that?"

"The slenderness of the hands."

"It looks like they are wearing a ghille suit."

"There's a white star or a void in the center of the mask."

"There is no visible flesh."

"The suit is very reflective."

When it seems like the room has spent themselves of things to observe, I told them that this was a still from a video piece, and this is what the still looked like when exhibited as intended:

I showed them the video, which the artist had very generously granted me access to the full-length work (of which this is an excerpt):

Nykelle DeVivo, Set You Free (trailer), 2025.

I read from a statement that I had received from Nykelle DeVivo when I wrote them inquiring about this work (of which little had been published owing to its recent creation):

The sequin figure in Duppy Conqueror and Set You Free is a Masquarede, which are suits used in ceremonies across the Afrikan diaspora as tools or vessels for Spirit (or ancestor) to manifest through. They are typically used in ceremonies to summon a specific Spirit to guide a community through lessons that can manifest as movements, dance, or performance. The Masquerade I’m referencing isn’t a particular Spirit but a stand-in for the collective rage and rebellion of Black ancestors. Activated by the wearer, the Masquerade acts through us as it (they) participate in acts of resistance. In Set You Free, that includes destroying a Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department police cruiser, symbolizing my family’s history with incarceration, as well as referencing the violence from the LAPD/LASD during the student protest of 2024. In Duppy Conqueror, the Masquerade wields an AK-47, a symbol of anti-colonial resistance from the Global South, firing what I loosely call “bullets.” These bullets are star fields created through solarization photography, with the center being a deep Black (w)hole. The hole references how, in the Afrikan context, the void is viewed as a space of “ultimate potential,” compared to Western perspectives where Blackness is seen as a space of lack. The spark of light around it alludes to the idea of the Flash Of The Spirit (first discussed by Robert Ferris Thompson), which states that Black people have long used reflected and refracted light as a portal for Spirit to enter. The bullets, fired from a tool for de-colonial resistance, are guided by Spirit and hold the potential to create new worlds. This is also why the Masquerade suit is made of reflective sequin/tinsel.

After they've heard from the artist speaking on what the work is, we have another conversation.

"The movements in the video look choreographed and fluid, not human."

"A sledgehammer is really heavy! The movement after the first strike as it circles back through the arm is graceful."

"The video feels cathartic, not angry. More like release."

"How did they get a hold of an LAPD patrol car?!"

"I hope they just found it somewhere, staged the video right then and there, and got away before getting caught."

"The suit when it's in movement with the video slowed is mesmerizing."

All of this can take a good chunk of time. I am not in a rush, and neither are they. They don't know each other, the room is still dark. Everyone's body language has shifted from the start of class, though. They are leaning forward, looking around towards whomever is speaking, making eye contact with each other, speaking back and forth, engaged. Better than any ice-breaker I could think of.

When I am at my best with social media, I sort what I'm most interested in into collections. On Instagram, one of those is "Artists to Keep Track Of." I keep this populated with whatever is hitting all my happy art alarms as I otherwise anesthetize my mind by endless doom-scrolling. And this is collection is the first place I consult when picking my #firstdayfirstimages. I do a different one for each class, each time. Right now this is a bit of what that collection looks like:

The second thing that I do is more discipline-specific. The assignment was gifted to me by my mentor, Elijah Gowin, when I first began teaching and panic-asked him for ideas for successful assignments. I'm grateful for Elijah's good-natured generosity in letting me in on enormously productive low-hanging-fruit enlightenment.

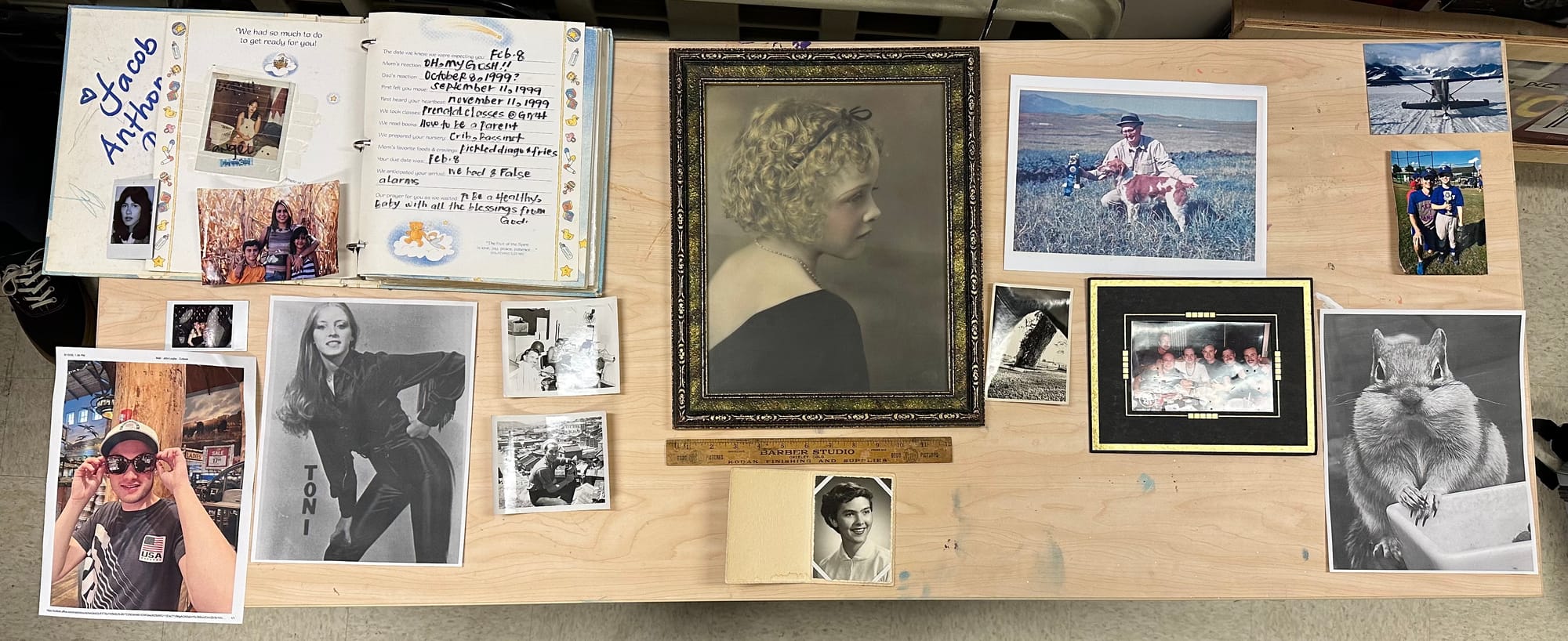

I tell them on the first day that we will have an assignment sometime later in the semester that will require them to bring the Oldest Photo They Have have to class, and to be prepared to talk about it. I further tell them that this can mean whatever it actually means to them at the time: maybe it’s a childhood photo, maybe it’s a family heirloom and they don’t know anything about anyone in it, maybe it’s a photo that was taken within the last year and lives on their phone. On the appointed day, I hand out an in-class reading by Douglas Nickel, “Snapshots: the Photography of Everyday Life.” After giving time for the reading, we circle the chairs so that we’re facing one another, talk briefly about the reading, and then start sharing the photographs and what we know about them, one by one. It is always the most revelatory and the best day of the entire class: I've heard incredible stories about one another’s relationship to photography, about who in the family is in charge of the image archives, about where their photos are and if they ever print them off their phones, about the power and importance of vernacular photography, about whether they stole any family photographs when they left home for the first time.

We will all take out our phones and do a round-robin confession of how many images are stored on our devices. I'm currently at 29,934. One student outdid me this semester with more than 56K.

One student showed up with a photo that they had actually made in the class. When we looked askance at him, he had an explanation ready: he was pathologically afraid of having his photo taken as a child. He had a twin brother, and their shared photo album would always have a picture of the one brother, followed by something "representing" him, say, a piece of pine-tree branch from a family camping trip.

Another student brought a hologram trinket with a face on it, and then shared that it was "funeral swag" from his grandfather's funeral, where everyone got this hologram key chain of the deceased for coming to the service.

Still another brought in a piece of paper they printed off in their dorm from Snapchat, and that sparked a long and enthusiastic discussion about the ethics of the platform, of screenshot images and getting notifications that someone took one, and I was riveted the entire time, since Snapchat fell into the generational divide for me after the Last Platform I Downloaded and Still Use.

Other students have talked about their family histories, about losing all of their photos to a divorce or other estrangement, about incredible inconceivable histories, such as Japanese great grandparents that did not get put into an internment camp during WWII because the great grandparent had served, or another banal looking photo of a young girl facing a pony, which was a student's great-grandparent the day before her parents were shot and killed during the Bolshevik Revolution.

The class is always permanently bonded with one another after this day, and something genuine and meaningful was exchanged both in feeling and fact. And I always participate as well, rotating between a series of images in my personal archive that I can always find something new to say.

These are just two examples of things that I do in the classroom that I have found success with. I don't like gatekeeping or otherwise silo-ing knowledge. Share something with me that you have had wild success with and that might transfer well to other contexts?